With the Cambridge City Council threatening a boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) resolution directed against Israel, I revisit and add to a message I wrote about our scriptural readings at this time last year—

The wondrous ending to the siege of Samaria narrated in our ancient scriptures this week is not a sound strategic model for our own times.

The wondrous ending to the siege of Samaria narrated in our ancient scriptures this week is not a sound strategic model for our own times.

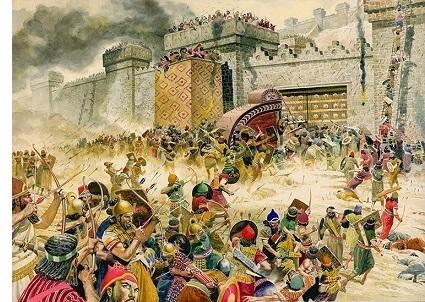

In the reading from the biblical Second Book of Kings that is paired with this week’s Torah-portion, the Israelites of Samaria wake one morning to find that the Aramean forces who have long laid siege to their citadel have suddenly vanished. Startled out of their wits by a phantom sound of chariots and horses in the night, the Aramean soldiers have abandoned their camp and all its provisions and have sprinted helter-skelter to the Jordan River and across it, eastward, scattering their gear and even their clothing along the path of their terrified retreat. (2Kings 7:3-20)

This, in the story, is a heaven-sent miracle – which, for any prescriptive, forward-looking, practical purpose is to say: a complete fantasy. “One does not rest one’s plans upon anticipation of a miracle,” says an ancient and frequent rabbinic adage. In the Babylonian Talmud’s tractate Shabbat (32a) the principle is taught this way: “One should never put oneself in a dangerous situation and say, ‘A miracle will save me.’ Perhaps the miracle will not come. And even if a miracle were to occur, one’s merit would be reduced.”

Today, the conflict – or say, the siege – stagnating on the West bank of the Jordan River – with varying perspectives, in the large and historical picture, as to who’s been besieging whom – is fueled by fantasies among each of the two peoples involved that the other will somehow effectively vanish. In actuality, neither Israel nor the Palestinian people is at all likely to disappear.

Last year at Harvard Hillel, the most recent past Director of Israel’s foreign intelligence agency, the Mossad, Tamir Pardo said: “Unless we find our way to a two state solution, it will be the end of the Zionist dream.” In another Harvard Hillel program, U.S. Ambassador Dennis Ross opined that Israel should build and settle strictly within lines that credibly allow for the emergence of an eventual, viable, dignified, and acceptable Palestinian state, whatever the Palestinian leaders and people and their supporters may do in the present. Those ideas, which eschew any notion that the other side in the present conflict will somehow go away, are as much a part of Israel and the visions of its broad political spectrum and discourse as is the biblical and historical bond between our people and the land.

Recently, lifelong political conservative and longtime World Jewish Congress head Ronald Lauder marked the occasion of the Jewish State’s 70th birthday by writing in the New York Times about “Israel’s Self-Inflicted Wounds”. This week, Israeli-born Natalie Portman ’03, who has screen-written, directed, produced, and starred in a film adaptation of Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness, in Hebrew, set in nascent modern Israel, has backed out of the Israeli Genesis Awards, explaining through a spokesperson, “Recent events in Israel have been extremely distressing to her and she does not feel comfortable participating in any public events in Israel.”

Some may celebrate Lauder’s and Portman’s statements and actions as evidence of a widening gulf between American Jews and Israel, a disappearance of allegiance. I see it differently. It is precisely because Lauder and Portman are each proud Jews, and Israel is integral in their identities, that they are troubled. Nobody should mistake the decision of either for evidence that a connection between diaspora Jews and Israel is vanishing.

I see a similar phenomenon here at Harvard, and a similar inclination, in the wider Jewish world, to suspect or even shoot the messengers. Virtually every Jewish young person I meet here has been raised to feel a sense of connection regarding Israel. Most feel a bond of identity with Israel, and for exactly that reason they feel accountable. With most raised to think of Judaism in terms of social justice, it is no wonder that many become alarmed when they read the predominating headlines about Israel.

My work is to increase understanding, to help our young people see the aspects and the parts of Israel’s complex society and democracy with which each, respectively, can identify, and to help as many as possible engage in constructive and hopeful ways with Israel, its promise and its possibilities. That can mean supporting a student-organized Israel Summit at Harvard showcasing the wonders and the advancements of Israel. And it can mean supporting students in confronting the issues about Israel that trouble them. The common factor is engagement, leaning in.

The boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement, by contrast, is all about alienating and ostracizing Israel, and the BDS manifesto is a recipe for ending the Jewish State. BDS aims to rally and convey a message of worldwide opposition to Israel. Anybody who thinks that is a formula for making the Jewish State go away should consider how well Israel has flourished amid adversity through the past seventy years. Unless either Lauder or Portman signs on to the BDS agenda – and I say that in one breath because I would be equally shocked if either were to do so – friends should not consider them to be a new enemies of Israel, and actual opponents of Israel should not consider them to have disappeared from among those who care for the state that bears our people's ancient and good name in the world. I hope nobody will mistake any part of the full spectrum of constructive and hopeful engagement with Israel that we practice here at Harvard Hillel for anything like the destructive and counter-productive strategy practiced by the BDS movement.

And, since the issue remains very much a live one in Cambridge this week, let me again append, as I did last time, the letter I have written to each member of Cambridge’s City Council:

Dear City Council Member McGovern,

As a Jewish Chaplain at Harvard University, I will welcome an opportunity to meet with you to discuss the boycott resolution against Hewlett Packard and against Israel proposed for consideration by the Council.

Especially as the proposal of this resolution seems to come from students and the academic quarter, I will be glad to discuss with you the array of constituencies and voices that exist on campus, and why – whatever position one holds regarding the Israeli-Palestinian situation and a desired outcome – tactics of boycott and alienation that single out Israel among all countries of the Middle East are manifestly ineffective, inflammatory, and counter-productive – they make a terrible impression of anti-Semitic prejudice on the part of local government, and are dreadfully damaging with regard to the good will and the atmosphere of the City.

Such proposals and resolutions generally amount to a shouting match among local interest groups; they have only a harmful effect with regard to the conflict in the Middle East itself; and such side-shows completely overlook the positive work toward peace that can be accomplished from places that have strong and active ties with Israel, as the Cambridge and Harvard communities do.

Parents around the country will hear from their children at Harvard what Cambridge does and decides, and the good name of this City stands to suffer or to flourish correspondingly. I will be very glad to think with you about constructive approaches to these important issues.

Respectfully,

Rabbi Jonah C. Steinberg, Ph.D., Executive Director and Harvard Chaplain